Modified COZY

N79ZR Accident Evaluation

Preamble:

As of September, 2015, sources inform me that we should expect the NTSB

final report on Zubair Khan's fatal accident (N79ZR) which occurred in July,

2014 within a couple of months - it's awaiting approvals from upper

management. In the meantime, through these sources that will remain unnamed,

I have come into possession of a rough radar track summary of this flight,

with altitude and timing information.

Analysis:

I've dissected the radar track, creating a table of position, forward

velocity and vertical speed vs. time. From this, we can also derive descent

angles. I've only calculated descent angles for the last part of the flight.

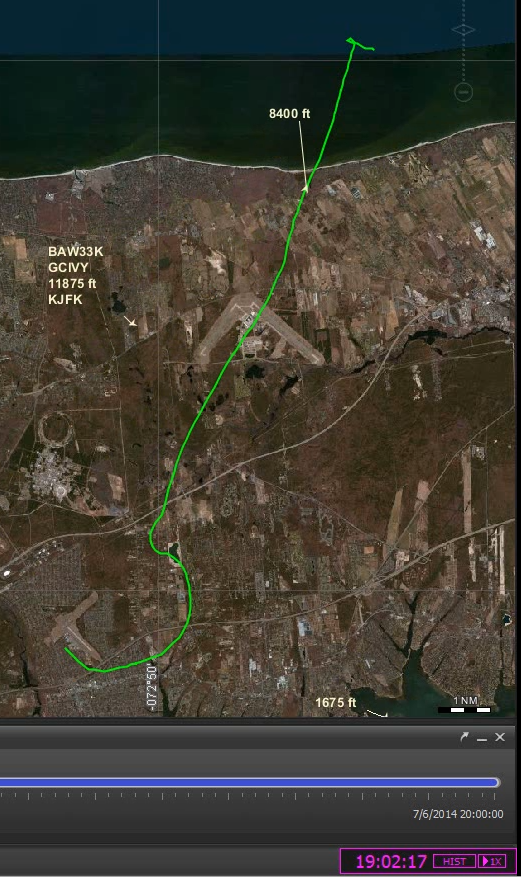

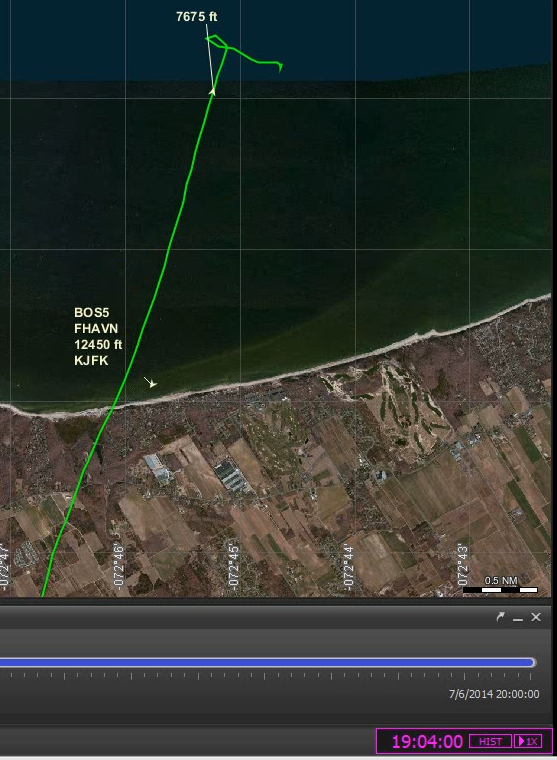

You can see the full flight radar track here:

showing Mr. Khan's takeoff from runway 15 at KHWV, and his climbout to the

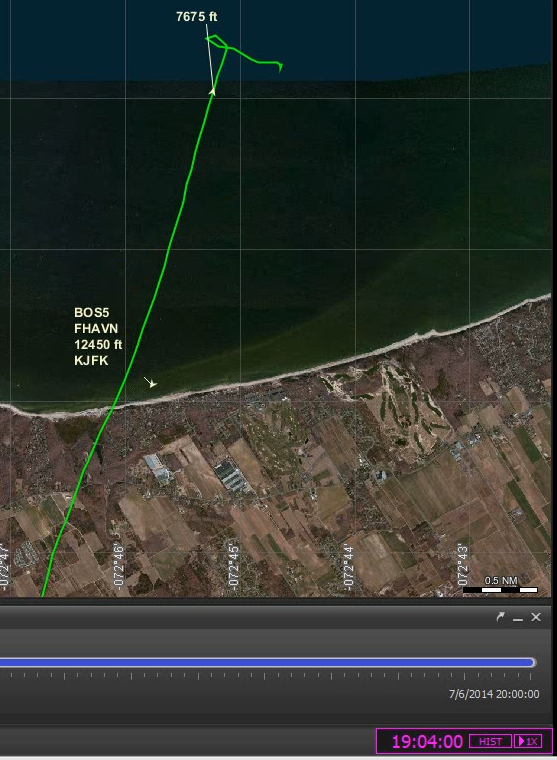

north-northeast over Calverton Airport. A closeup of the later portion of

the flight is shown here:

Showing the portion of the flight over Long Island Sound, north of the

shoreline.

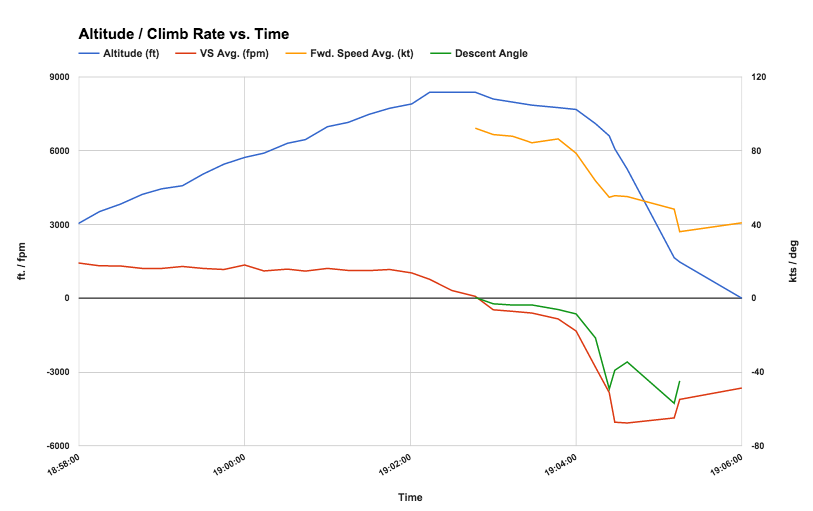

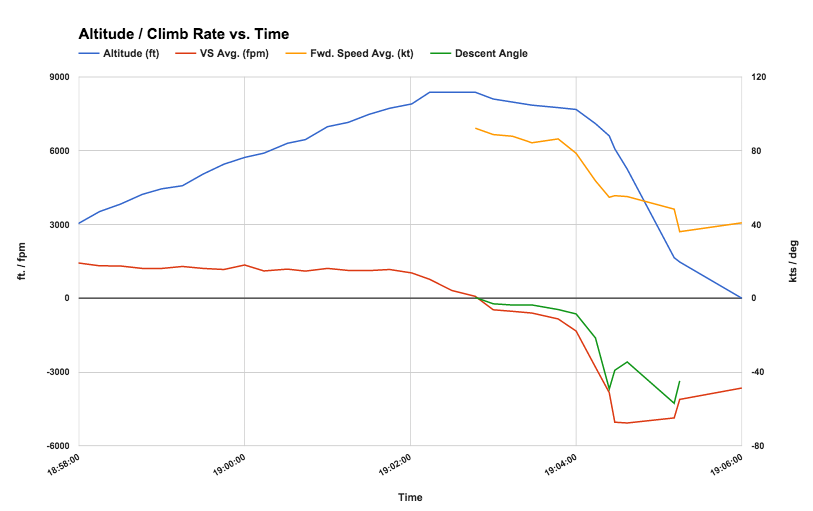

I've graphed the calculated data derived from the radar track vs. time:

The left vertical scale indicates altitude and vertical speed. The right

vertical scale indicates forward velocity (starting at 19:02:47) and descent

angle. The raw data is rough - taken from the radar track with a scale, with

jumpy altitudes and positions. The speeds are GS, not TAS or IS (since

they're from radar), but even with +/- 5 to 10 kts error, the indications do

not change. With a bit of smoothing, the basic picture is clear - the #'s

are right to within 10% - 15% or so.

Mr. Khan performed a steady climb up to approximately 8400 ft., while

heading north-northeast over Long Island and out over Long Island sound,

just north of the Calverton airport. Once over the water, he slowed the

airplane to approximately 90 kts. Soon after the aircraft began a steep left

turn of 270 degrees along with a high vertical rate descent, which very soon

became a descending straight line flight. The average descent rate during

the turn and straight flight was about 5K fpm with an average forward

velocity of about 50 kts. This gives a descent angle of approximately 45

degrees degrees, with a total velocity of approximately 70 Kts.

Soon after loss of radar coverage, the aircraft impacted the water.

Interpretation:

While a higher descent rate than that calculated/measured by RAF for a

Long-EZ (approximately 3500 - 4K fpm), the relatively slow horizontal speed

along with the high descent rate and large descent angle clearly indicates a

deep stall condition, particularly given the 3/4 mile long straight flight.

The flight profile shown by the radar track cannot be supported in any other

flight regime other than a deep stall - a 45 degree descent rate in normal

flight would very quickly build to extremely high speeds - speeds which did

not develop here and in fact, may have decreased a bit over time.

Mr. Khan was probably killed or incapacitated by canopy impact fairly early

on in this timeline, probably just before or soon after the tight turn and

deep stall developed, as he attempted to egress the aircraft by ejecting the

forward hinged canopy. This implies that the straight portion of the flight

occurred (in a non-spiral stable aircraft) without ANY

pilot input - another indication of a very stable deep stall condition.

As of April, 2014, Mr. Khan had not installed the leading edge vortilons on

his aircraft (I had told him at that time not to perform stall testing prior

to installing the vortilons). From other pilots at Mr. Khan's home airport,

we know that he had not installed them as of the date of the flight.

COZY aircraft N79ZR had been stretched 8" between the canard and main wing

by the original builder (not Mr. Khan) and had only a rough estimate for CG

range recommendation (I was assisting Mr. Khan with this task and was having

extreme difficulty getting accurate information from him, as well as getting

him to understand all the issues). It also had a substantially stretched

nose forward of the canard, which, with the extra width of the COZY aircraft

over the Long-EZ aircraft, was especially problematic at high AOA's with

respect to deep stall (and stability, but that wasn't the problem here).

This aircraft had two sets of fuel tanks - standard strake tanks about 6"

aft of the theoretical CG range (due to the forward move of the CG range

from the stretch) and a smaller fuselage tank approximately 20" - 25" FORWARD

of the theoretical CG range. Managing CG position in this aircraft would

involve a large pilot workload and the calculations of both theoretical CG

range and actual CG position were not well formed. With a forward tank so

far from the acceptable CG range, burning fuel from the forward tank would

move the CG aft very quickly. We do not know from where fuel for the flight

was drawn, but we know that Mr. Khan (from airport records) had either

topped off the tanks or come close to doing so before the flight.

Conclusions:

As aft CG and lack of vortilons are two large contributors to deep stall

susceptibility (and have factored into at least one previous COZY deep stall

incident, in 1996), Mr. Khan's decisions not to install the required

vortilons and to stall test an airplane in which the CG range (and CG

position) was poorly understood and controlled were not good ones.

So there is little new to learn from this accident - really, all we can

learn are things we should already know, but I'll reiterate them here:

- Understand and carefully determine the Acceptable CG range for

YOUR aircraft (particularly if it's in ANY way non-standard)

- Understand the CG location for YOUR aircraft on ALL

flights - ensure that you are ALWAYS inside the

approved AND TESTED CG range

- Install all required aerodynamic safety items, including the

vortilons, lower winglets, etc.

- Understand the effects of fuselage stretch (or width increase), both

between the lifting surfaces and forward of the canard, and approach any

change of this nature with EXTREME caution

- Listen to knowledgeable people when they give you solicited (or even

unsolicited) advice regarding safety (where "Listen" means "act on it",

not just "nod your head and ignore it")

- Be extremely careful when making (or accepting previously made)

aerodynamic and/or structural changes to ANY aircraft

that were not approved by the designer - do not think that "it will be

OK" merely because you want it to be

- Do not fall into the "sunk cost" fallacy - just because you've thrown

a lot of time and/or money at an airplane project doesn't mean that the

right answer is to keep doing so, if there are major problems with it

Addendum:

I liked Zubair - Deanie and I had dinner with him in April, 2014, after I

examined his aircraft and spent the afternoon with him. He was bright,

engaging, interesting and kind. He was dogged, and extremely hard working.

None of that mattered - everyone who dealt with him and attempted to help

him modify and fly his aircraft safely believed this outcome, if not

pre-ordained, was at least extremely probable, given the way he approached

the process. He seemed incapable of actually listening to what knowledgeable

people were telling him over the course of the approximately two years since

he purchased the project and worked toward flying it.

Just very sad - moreso for his family and those that loved him.

Return to: Cozy MKIV Information

Copyright © 2015, All Rights Reserved, Marc

J.

Zeitlin

e-mail: marc_zeitlin@alum.mit.edu

Last updated:October 2, 2015